In recent years, high-profile cases of white-collar crime have shaken our trust in the institutions we once looked up to. From the billionaire antics of Sam Bankman-Fried, whose alleged fraudulent schemes shook the cryptocurrency market, to Elizabeth Holmes, whose biotech aspirations dissolved into scandal, such narratives evoke visceral emotions. These are not just stories of misdeeds; they unveil a systemic issue within the tech and finance sectors — a culture that often prioritizes ambition and profit over ethics. Strikingly, these modern-day con artists leave victims—their crimes often preying on the vulnerable, such as elderly individuals losing their savings to deepfake fraudsters.

What connects these disparate tales is the alarming ease with which individuals can manipulate systems for personal gain, not just in technology but across various sectors. This growing trend forces us to reconsider the nature of crime and deception. How did we arrive at a point where deceit seems as ingrained in corporate culture as innovation?

The Life After Crime: From Inmate to Insider

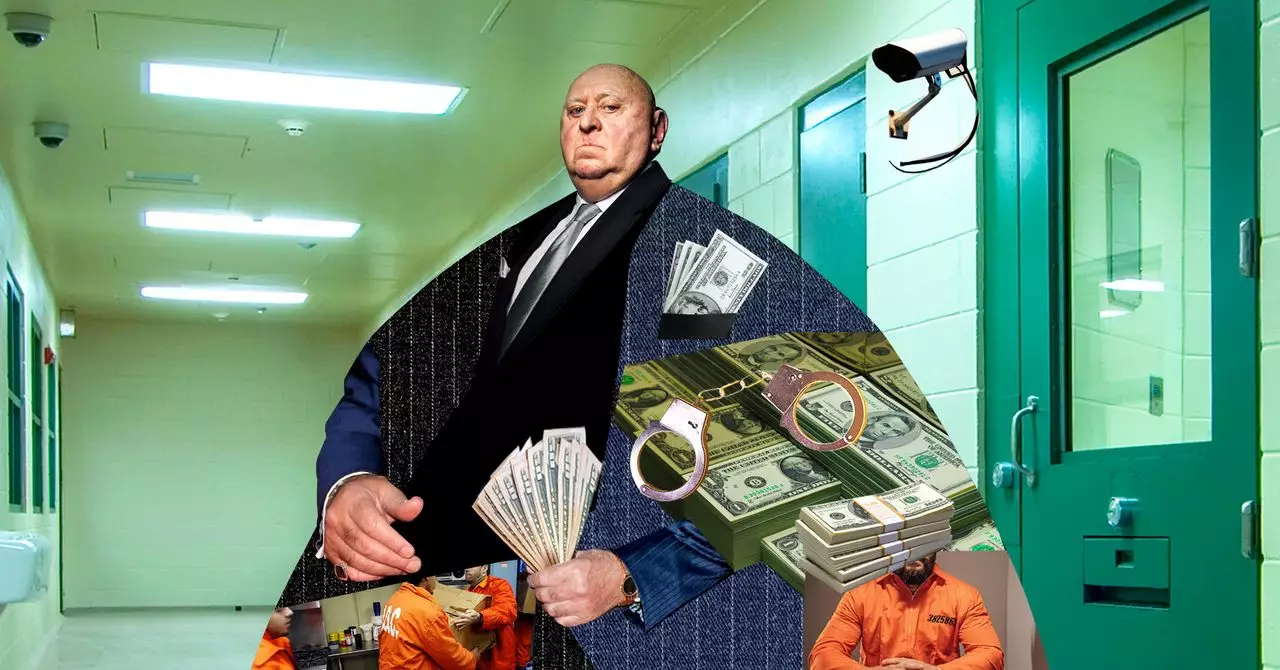

One intriguing response to the rise of white-collar crime is the emergence of consultants who navigate the blurred lines between legality and morality. Take, for instance, a former prison inmate who has transformed his incarceration experience into a consultancy business aimed at guiding white-collar criminals. Surprisingly, his story is both darkly humorous and profoundly tragic. He employs a sharp, no-nonsense approach to assist his clients in managing their prison sentences effectively. He describes his former life in prison not with regret but with a sense of mischief and control, revealing a deep understanding of human psychology.

His ability to manipulate situations became a skill rather than a vice. With anecdotes of diverting attention and bending authority to his will, he showcases a messiah-like bravado within the bleak infrastructure of penitentiaries. Yet, beneath the bravado lies a troubling implication: this adaptability and cunning, while seemingly harmless in his context, reflect traits that often define white-collar criminals. In his new role, he cultivates a persona that straddles the line between perpetrator and savior, offering a perverse kind of legitimacy to those engulfed in shame.

The Emotional Toll of Fraud

For many individuals ensnared by white-collar crime, the mental cost is staggering. Experience tells us that financial fraud not only results in monetary loss but triggers a cascade of emotional turmoil—shame, fear, confusion, and anger. The prison consultant’s clients frequently embody this troubled spectrum. They arrive at his door desperate for guidance, grappling with the imminent consequences of their actions. The consultant’s methodology involves both tough-love and practical advice, as he recognizes that this unique emotional landscape is crucial in reshaping their narratives and ultimately influencing their time in prison.

Interestingly, this approach highlights the paradox of accountability in white-collar crime. Where traditional criminal behavior might sidestep scrutiny due to its nature as ‘fine print’, white-collar criminals often have to confront the emotional aftermath head-on. The stakes are high; their reputations, financial security, and social status hang in the balance.

The Business of Rehabilitation

The consultant underscores an ironic truth: there’s significant profitability in helping individuals navigate the repercussions of their white-collar crimes. With fees ranging from a few thousand to upwards of $50,000, he denotes a strange capitalist circle—wherein committing a crime can inadvertently spawn a new avenue for financial success. This new industry, sprouting from the roots of deceit, calls into question the ethics regarding who profits from wrongdoing.

It’s unsettling to imagine that criminality can morph into a professional path, feeding off the vulnerabilities of others. The burgeoning field of prison consultancy could be seen as a troubling paradox, as it inadvertently celebrates the very behavior it seeks to correct. In the grand scheme, should we not be concerned that the line between prevention and profiteering has become perilously thin?

By examining this multifaceted world, we confront not only the consequences of wrongdoing but also the systemic issues that enable such behavior. In an era dominated by technological advancement and rapid economic change, how we understand and react to these truths will shape the future of justice itself.